“The war is still being fought” in Burkina Faso’s East; its impact on the population deepening

On 15 September 2019, Salif Koadima* fled his home in the village of Soam (Matiacoali commune, Burkina Faso), where his family had lived for over 44 years. Earlier that day, he had received news that unidentified armed men, to whom he referred simply as “jihadists,” had assassinated his neighbor for reasons unknown to him. A councilman in Matiacoali’s city council, he knew he was in imminent danger, with local authorities being a main target of armed violent extremist groups active in the region. Within the hour of learning of his neighbor’s assassination, he had left the village, reflecting, “[when] you have heard something like this, you don’t wait around for your turn.”

Koadima left his village by motorcycle to settle in Fada N’Gourma, capital of Burkina Faso’s East region. He chose Fada N’Gourma over his commune’s chef-lieu of Matiacoali, as the latter remained too dangerous, deeper into the areas where violent extremists continue to roam with relative liberty. For him, Fada N’Gourma was the more secure option and the one with greater opportunities to access support. Upon arriving, Koadima settled in the city’s Sector 1 neighborhood with a distant friend of his extended family. He wasn’t able to call his soon-to-be host family to let them know of his imminent arrival. Evacuating from Soam as he did, his sole focus was leaving. Koadima knew it wouldn’t be an issue, though, “that’s just how it is, here, you can’t refuse someone in this kind of situation.”

His family, 4 wives and 21 children and grandchildren, joined him in Fada N’Gourma five days later. Due to the presence of violent extremist groups in and around Soam, the minibuses and motorized tricycles typically providing transport services in the area had disappeared. The transporters, too, were seeking to avoid confrontation with the armed groups. As such, and without other options, his family walked the nearly 25 kilometers from their family home to the nearest main road: National Route 6, the pot-holed strip of pavement connecting Fada N’Gourma and Matiacoali. From there, they were able to take a minibus to join Koadima in Fada N’Gourma. Upon arriving, they split between two host families, given their large number.

Over the past few years, hundreds of families like Koadima’s have been forced to leave Soam and settle in nearby cities as a result of violent extremist activity. Not far from the village of Tanwalbougou, a frequent flash point between violent extremist groups and local security forces and militia, Soam has been hard hit by the ongoing conflict in Burkina Faso. At the end of March, militants ambushed a local militia unit in the neighboring village of Mourdéni, resulting in several casualties [1]. In Soam proper in mid-February, presumed Islamic State- or al Qaeda-linked fighters burned grain stores in alleged retaliation for the village moving to establish a local militia unit [1].

More broadly, Burkina Faso’s East region continues to be an important military theater in the country’s battle against violent extremism. Thus far in 2021, there have been 42 security incidents in the region involving known and unknown extremist groups, largely the West African affiliates of the Islamic State and al-Qaeda [1]. These incidents have resulted in at least 22 fatalities, nearly 3x less though than during the same period last year [1]. Some link this down tick to recent intensification of military interventions in the region [2]. Others draw links to reports of negotiations between the government and violent extremist groups, speaking of an unstable ceasefire [3].

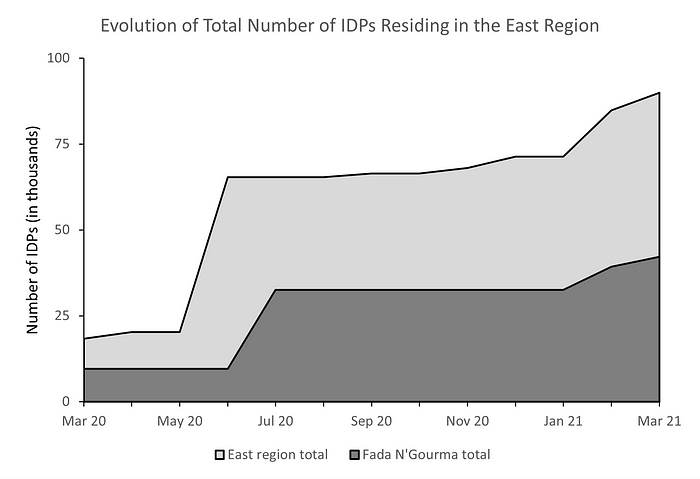

While the number of fatalities may be trending downward, the impact of the ongoing conflict on the East’s population continues to be overwhelming. As a result of violent extremist activity in the region, nearly 90,000 individuals have left their homes and settled elsewhere as of 31 March [4]. A large proportion, over 46%, of these now Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) are living in Fada N’Gourma, including Koadima and his family [4]. For many, it will take more than media reports of fewer killings to return home. And, in the interim, many will continue to need direct support, especially as aid program budgets dwindle.

Since arriving in Fada N’Gourma, Koadima has been without work, relying on donations to meet his and his family’s basic needs. A farmer and cattle herder like many in the East, fleeing from Soam has meant leaving not only his home, but also his main source of income: his fields. For Koadima and his family, support has come mostly from the government’s social security department, family friends, and several international NGOs operating in Fada N’Gourma. So far, they have received sacks of corn, balls of soap, a tent and mats, and coupons for medications. Of the donated food, only two sacks of corn remain, enough for about two weeks.

For Koadima, the first few months after leaving Soam were the most difficult, as accessing support through aid programs was complicated. In late September, shortly after arriving in Fada N’Gourma, he approached the government’s social security department to register as recently displaced, the first step in accessing government-directed aid programs. Only two months later did the department contact him indicating a time and place for his family’s registration. The government’s registration processes have been criticized by aid agencies for this reason, as impeding the efficacious management of aid distribution to those in need. Koadima received his first support through the government in December 2019.

The support Koadima has received has prevented his family from experiencing severe distress, but their needs persist. He noted that the people in need are numerous, especially in Fada N’Gourma. As a result, the aid received is not the same for everyone; there isn’t enough to go around. When asked of his family’s greatest needs now, he responded food and cash. With the cash, he would like to construct a house, something more permanent, as they are still sheltering under UNHCR-branded plastic tents.

While grateful for the support his family has received so far, its passive nature is beginning to affect his dignity. He shared, “if you have been lucky enough to receive support, you don’t question it, you thank God that you’ve received it.” He expressed, however, that as a head of household, to only be able to provide for his family’s needs through donations, is a deception. He wants to earn his income. His greatest wish is a job, so that he can end his passive dependence on others and take charge again of his and his family’s trajectory. While some aid organizations have adopted cash-based interventions, they remain limited. Cash-for-work programs are nearly nonexistent.

Nearly two years since leaving Soam, Koadima said he will wait until the war is finished before deciding to return to his village. While he says he has noticed an improvement in the situation between last year and now, hearing then of tens of people killed per attack and now only of a few,

he says “the war is still being fought.” He still receives updates from those who have stayed in Soam, and from them, he hears it is not safe to return. Just the week prior, his contacts let him know a group of ten violent extremists passed through the village. The news came as a sign the threat that forced him to evacuate remains, extending his leave of absence from Soam.

As the war stretches on in the East, Koadima and his family, and the thousands of other families like his, are being held in limbo. The passing time is deepening the impact of the conflict on them and wearing thin the resources they have to cope. As the conflict continues without a clear end in sight, these families and their shifting needs deserve continued focus, as they are the ones bearing the brunt of this storm.

To support response efforts to the current humanitarian situation in Fada N’Gourma and the East region, please consider contributing to Initiative: Eau.

*names changed or omitted for privacy

References:

[1] Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre and Joakim Karlsen. “Introducing ACLED-Armed Conflict Location and Event Data,” 2010

[2] Wilkins, Henry, “What is behind the sharp drop in deaths in Burkina Faso’s war?”, 07 April 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/4/7/armed-violence-in-burkina-faso-declines-in-past-year

[3] Mednick, Sam, “Burkina Faso’s secret peace talks and fragile jihadist ceasefire,” 11 March 2021, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2021/3/11/Burkina-Faso-secret-peace-talks-and-jihadist-ceasefire

[4] SP/CONASUR, IDP Situation by commune, 31 March 2021, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_lIS6MYUQSv_EJyuos0c6_gN9BybR2cn/view